Autores: Tom Aston, Florencia Guerzovich and Alix Wadeson

As we illustrated in the previous blog in this series, funders, fund manager organisations and implementing organisations in the Transparency, Participation and Accountability (TPA) sector are wrestling with the challenge to move beyond piecemeal project-level MEL to evidencing more cohesive programme and portfolio-level results which are greater than the sum of their parts. This is the holy grail, as Sam Waldock of the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) put it in the Twitter discussion.

Some grounds for optimism

While we agree that portfolio MEL is challenging, it’s not impossible. Some efforts in the wider international development sector give us reasons to be optimistic when there is political commitment at the right level. As CARE International’s Ximena Echeverria and Jay Goulden explain, it’s possible to demonstrate contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) across an organisation with over 1,000 projects per year. With standard indicators, capable staff, and serious effort, you can assess progress at a considerable scale. But there are also ways to break such enormous portfolios down into more manageable chunks.

One of us conducted a review of CARE’s advocacy and influencing across 31 initiatives (sampled from 208 initiatives overall) that were relevant to just one of CARE’s 25 global indicators up to 2020. This was based on a Reporting Tool adapted from Outcome Harvesting (a method which is increasingly popular in the TPA sector). CARE has continued to assess this in subsequent years, looking at 89 cases last year because it saw the value in the exercise. As advocacy and influencing constitutes roughly half of their impact globally, it’s obviously worth evaluating and assessing whether trends of what worked changed over time. Oxfam was also able to do something similar for its advocacy and influencing work, building off 24 effectiveness reviews (which relied on a Process Tracing Protocol; if you’ve read some of our other blogs, you’ll know we’re fans of this method).

Both reviews, also similar to the Department for International Development’s (DFID) empowerment and accountability portfolio review of 50 projects, were Qualitative Comparative Analyses (QCA) — or fuzzy-set QCA. We believe that QCA is a helpful approach to find potential necessary and/or sufficient conditions, but such conditions are not always forthcoming (as DFID’s review showed); they also rely heavily on the quality of within-case evidence. We’re often searching for, but not quite finding, necessary and/or sufficient conditions. For this reason, there are limits to what QCA can do, and without adequate theory it can sometimes be premature.

Realist syntheses (or realist-informed syntheses) also provide a helpful option to assess what worked for whom, where and how. The “for whom” question should be particularly of interest for the Hewlett Foundation’s new strategy refresh as well as to all colleagues who strive to design portfolio MEL systems that are useful to its different stakeholders and decision making needs. One great benefit of the approach is that it assumes contingent pathways to change (i.e., diverse mechanisms), emphasizing that context is a fundamental part of that change rather than something to be explained away. A more contingent realist perspective thus builds in a limited range of application for interventions (x will work under y conditions) rather than assuming the same tool, method, or strategy will work the same everywhere (the fatally flawed assumption that brought the sector to crisis point).

The Movement for Community-led Development (MCLD) faced a similar “existential threat” as the TPA sector — after another hot debate about the mixed results of Community Driven Development (CDD) in evaluations. Colleagues from 70 INGOs and hundreds of local CSOs from around the world, started a collaborative research including a rapid realist review of 56 programmes, to understand the principles, processes, and impact of their work. They counted on leadership and some external funding, but often relied on voluntary time and good will. The process and the results include several relevant overlaps and insights for monitoring and evaluating portfolios of TPA work. The full report is due to be published on the 6th October, 2021.

As observers and participants in the MCLD process, we would like to underscore a factor that distinguishes this effort from many others — don’t ignore the “L” (learning). Regular calls among the group were made to engage in a kind of “social learning,” resembling a learning endeavour which is described by the Wenger-Trayners as an ongoing process which creates a space for actors to mutually exchange and negotiate at the edge of their knowledge, reflecting on what is known from practice as well as engaging with issues of uncertainty.

In the TPA space, where practice often entails advocacy grounded in expertise and/or values, including to set research and learning agendas, creating this learning space requires, at a minimum, changing the mindset and challenging normative assumptions and apparent agreements that constrain social learning. For another call to put “L” front and centre, see Alan Hudson’s feedback to the Hewlett Foundation’s strategy refresh.

Therefore, with sufficient political commitment and flexibility, the appropriate methods and processes are out there to assess and support social learning in as few as 5 to as many as 1,000 cases or initiatives. But there also seems to be a more meaningful sweet spot somewhere between assessing a group of 5 and 50 initiatives.

How can portfolio evaluation contribute useful knowledge to the field ? The GPSA’s journey

We’ll discuss an example of a funder the three of us know well (but do not speak for), one that has been unusually open about its complex MEL Journey. The Global Partnership for Social Accountability (GPSA) started grant-making in 2013; by 2014 it had already designed 20 flexible grants tackling a broad range of development challenges (health, education, public financial management, etc.) in diverse contexts — from Mongolia and Tajikistan to Ghana and the Dominican Republic. The common thread for these grants was that, a priori, they were all cases that it was judged would benefit from politically smart collaboration between public sector and civil society actors. The prioritisation of a problem and the precise approach and tools to tackle challenges themselves was localised.

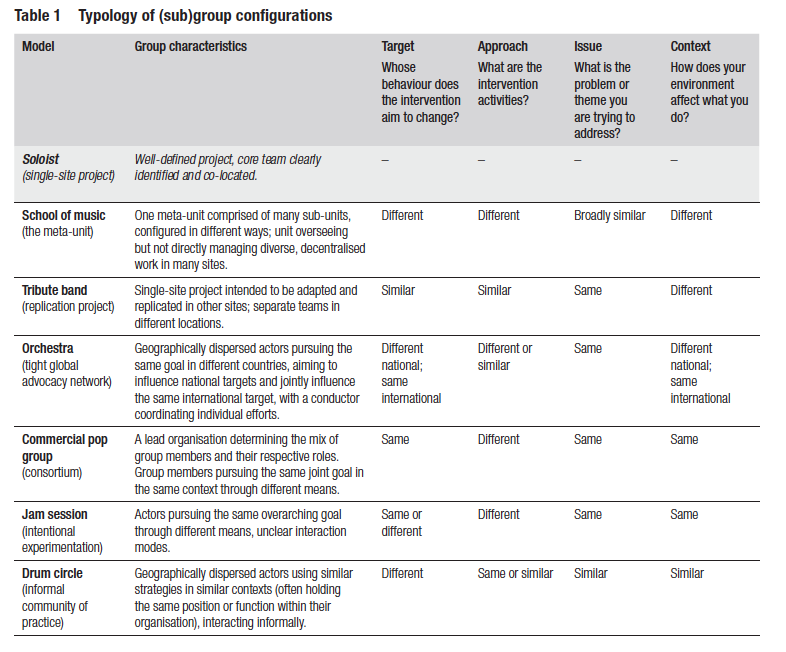

In its infancy, the GPSA lacked a comprehensive MEL system. The programme prioritized grant partners’ ability to determine on their own appropriate approaches to MEL and aggregation of results was less pressing. “Learning by doing” is something of a mantra at the GPSA whereby both the GPSA and its grant partners are expected to embrace this approach. It encourages (uncommon levels of) openness about failures and allows ample room for iteration of collaborative social accountability processes undertaken by diverse grant partners across over 30 countries (to date). To pick up Bowman et al.’s typology, by 2016, MEL was a full-blown “jam session” among grant partners that resemble other decentralised systems (see the typology below).

Bowman, et al. 2016

One practical challenge was that the GPSA had questions about the aggregation of results. The onus, as affirmed by former World Bank President Jim Kim, was to show that this “miracle” has real outcomes. Delivering on this challenge could go in different ways. As elsewhere, finding and implementing a compromise among decision-makers needs across the system is easier said than done or resourced.

Over the years, the GPSA explored the implications of adaptive learning as a fundamental portfolio approach while responding to this demand, it intentionally experimented over time for gradual design, implementation, and course correction. A careful dance while fitting in World Bank rules, processes, and shifting approaches and norms.

A key part of this journey was about transforming the free flow ‘jam session’ into a more harmonious school of music. The latter is an entity that includes a wide range of activities (instruments) implemented by multiple, diverse grant partners (music school members) that have a loosely defined common theory of action to work in diverse contexts to tackle a range of development problems (different musical genres and sheet music). The GPSA, along with funding partners and World Bank management sector and country staff, makes initial choices in this regard — which is why strategy refresh season is important. They also provide financial and non-financial support and also can facilitate information exchange and compile activity reports for higher ups. Yet, the portfolio’s day-to-day work is often decentralised, and line-managed by people in other organisations (grant partners). The GPSA, like other funders or fund managers, often has limited authority to direct the behavior of partners — but it’s not innocuous and thus should not be omitted or obviated from the story.

The GPSA is building upon layers of ‘jam session’ lessons to shape a school of music-type portfolio that can start to play more harmoniously under the direction of a MEL system developed over time. This has been a multi-year process in which “L”, in the sense described above, was front and centre in the GPSA’s criteria for funding applications, annual reports, revised theory of action and indicators in the results framework. It’s also more explicitly emphasised in GPSA’s annual grant partner forums — GPSA alumni participate in these events which enables retrospective insights and facilitates that ongoing engagement and support across civil society can be maintained over the longer-term, beyond the duration of a grant. The GPSA also hosts other virtual events and bilateral conversations.

Connecting the dots across these MEL tools, in 2016, the GPSA began to articulate key concepts ‘for the practice from the practice,’ such as collaborative social accountability. The GPSA needed a new common language to talk about and understand the work — what looks like yet another label, was an effort to avoid cacophony. In 2018, the GPSA agreed to “test” key evaluation questions of interest to different stakeholders, with a small number of evaluations (Expert Grup took the plunge first). Then, the GPSA learned that the priority of these questions resonated with grant partners as well. In 2019, grant partners watched presentations of 4 evaluations and came back to one of us saying: “now I understand what you mean that an evaluation can be useful, I want one like that!” Part of the trick here is that those select evaluation questions were also useful to management, and a broader group of Global Partners.

Social learning within the school of music informed the next iteration of MEL tools, including refining the evaluation questions, and others that can support us to better grasp the elusive question of ‘what does sustainability and scale of social accountability look like in practice?’ All this MEL work and social learning with partners about practice precedes the current GPSA Manager, Jeff Thindwa’s, call for the field to take stock, match narratives to the work, and write the next chapter for social accountability. We agree that this kind of social learning is key to exploring TPA theories of action and change, develop tools to assess them, and hopefully will help us to challenge the doom and gloom narrative. In a slightly different guise, social learning underscores the importance that the principle of utilisation-focused evaluation should be a key priority (rather that its specific methodological incarnations, per se), which has been reasserted in recent evaluation discourse (for instance, as a central theme at the Canadian Evaluation Society’s 2021 annual conference).

In the next post of this series, we’ll share more practical insights about the design of MEL systems emerging from our work across different portfolios. These are insights that we believe are useful for different types of schools of music as well as for colleagues who privilege any of the methods discussed above and/or support the idea of a bricolaging them.