By Florencia Guerzovich and Paula Chies Schommer

(*para versão em português, clique aqui)

A Rio de Janeiro tale: citizen’s awareness by other means

On November 2018, Rio de Janeiro’s Luis A. Pezão governor was imprisoned due to corruption and money laundering charges. The case is a reminder that the Car Wash operation is still unfolding, as is the political, technical and legal battle for the survival of its results.

The Pezão case is also a reminder that power holders are still trying to sustain the status quo:

- Pezão was allegedly sustaining the criminal organization formerly led by his predecessor Sergio Cabral, which included among other illicit, bribes for public officials in state control bodies. As Professor Mauricio Santoro noted: Every governor elected from 1998 to 2014, every president of the state’s legislative assembly (1995 to 2017), 10 out of 70 state legislators, 5 out of 6 counselors in the state’s Court of Accounts and the Attorney General of the state have been jailed. Please note, this crowd largely belongs to MDB Party – rather than Luis Inacio Lula Da Silva’s Worker Party.

- Michel Temer (MDB), outgoing president of Brazil, has issued a pardon that would let many of his allies out of jail (a tool used in other contexts for similar purposes). The Brazilian Supreme Court was discussing the constitutionality of the pardon on the day Pezão went to jail.

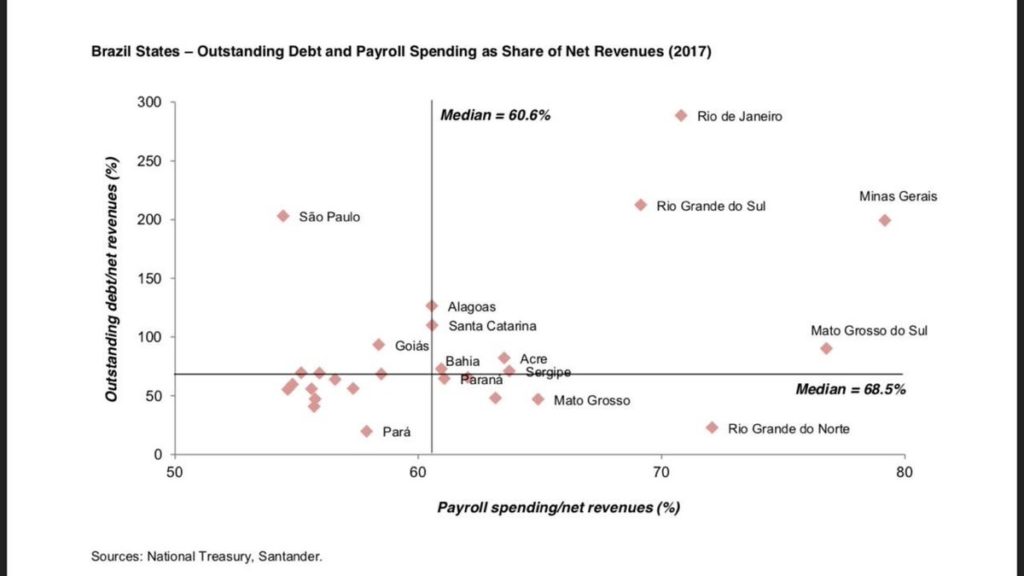

Two years before, one of us was living in Rio de Janeiro on the day the previous state’s governor Sergio Cabral (MDB) went to jail in 2016 (he has been found guilty of money laundering and corruption multiple times since then). That morning on a public bus, the driver yelled and honked to the newspaper guy in the corner: Cabral is in jail! The driver referred to the dire situation of public services and security in the state. Rio de Janeiro’s fiscal situation was and is dire, even in comparison with other Brazilian states (see graph below).

That morning in a Rio de Janeiro gym, in true Carioca spirit, music was loud and fun. A group of pensioners were at once celebrating and pining over the news about Cabral’s imprisonment. They also talked about the police’s lack of basic resources (paper and gas) to provide security, the crisis of public education, and the lack of medicines in the public health system. For @shannongsims the scene would be repeated three years later.

An anticorruption advocate’s “dream” scenario: people in the street making the link between corruption and their daily lives. We heard Brazilian commenting the news in the beaches of Joao Pessoa, in the northeast, and Florianopolis, in the south. No advocacy campaign had been necessary to get the conversations going. Or at least not a traditional civil society organization-led campaign. Civil society in localities across Brazil were turning anger into different forms of action – from manifestations to social accountability.

The judiciary’s role in communicating what enables corruption and its effects

If people did not realize through campaigns that corruption affects their lives and kills, judges and prosecutors have consistently made the link between the state’s fiscal crisis, deficient service delivery and the corrupt organization under investigation. The causal link between corruption and the public interest appears in judicial documents, it is reinforced in messages in press conferences, and in social media. Car Wash’s main prosecutor has argued that “corruption is a serial killer that is disguised as holes in roads, lack of medications, street crimes and poverty.” Car Wash’s Judge in the State of Rio de Janeiro argued “corruption is the main cause of the state of calamity (due to the fiscal crisis in Rio).”

Supreme Court Judge Luis Alberto Barroso argued against Temer’s pardon stating that corruption is a “violent crime”. Corruption “kills in the queue of the Unified Health System, kills through the lack of beds in hospitals, kills in the absence of medicines, kills roads without proper maintenance. Corruption destroys lives that are not adequately educated due to the absence of schools.” Using development language, Barroso made the link between corruption and human capital (#investinpeople). Barroso was speaking to his Brazilian audience – his colleagues in the Court, prosecutors that advance against all odds, and society that is supporting anticorruption change.

Barroso’s argument in the Supreme Court’s plenary was cast in national TV and multiplied in social and traditional media 1000s of times. He mentioned that there are three groups who will not hear his message: a) “part of progressivism in Brazil thinks that the ends justify the means and corruption is a footnote in the history of Brazil;” b) “part of the conservatives think that corruption, if it is of the conservative colleagues, there are no problems,” c) “there is the ones that do not want to be punished ….there’s a worse lot in Brazil: it’s the ones that do not want to be honest even moving forward, and they want everything to be as it always has been.” As Constitutional scholar Roberto Gargarella has argued, thinking beyond retribution, Car Wash is providing an unprecedented opportunity to communicate and enable public acknowledgement of the mechanisms that underlie public life. In Brazil, we have noted that judicial operators seem to be changing their communication practices accordingly.

We know little about why and how people mobilize against corruption once they acknowledge the state of affairs. A forthcoming paper by Francis Fukuyama and Francesca Recanatini argues that anticorruption initiatives, mainly focused on measurement, have basically failed. Corruption is essentially political – a challenge for judicial operators who have to be and appear to be non-partisan in the game. Anticorruption advocacy campaigns are often designed without clear understanding of whether the assumptions we make are relevant, overly ambitious or counterproductive.

Four evaluations challenging anticorruption groups to rethink advocacy

A group of evaluations of Transparency International’s advocacy in different contexts argue that civil society groups need to develop new types of advocacy campaigns. Campaigns that are relevant for citizens and elites (increasingly) aware about corruption’s effects. An evaluation of the “Unmask the Corrupt Campaign” found that the campaign was able to builds expectations of actions & results (justice) early on. However, it didn’t deliver on the promise, meaning the campaign ultimately breeds disillusionment and disengagement.

Flores and co-authors present “a three-level model that captures the micro, meso, and macro factors that affect individual decision-making, including the sequence in which individuals process information and —subsequently — evaluate and re-evaluate whether to take action against corruption”. They argue that the model can help domestic actors systematically try out, reflecting on, and adapting their strategies for stimulating citizen engagement. It can help international actors provide more adequate backing for these processes. For the authors, activists working in disillusioned contexts face a different, often uphill battle than those that work in apathetic or optimistic ones.

A 2018 evaluation of TI’s global advocacy argues that “it is worth celebrating success in establishing anticorruption agendas, commitments and institutions. At the same time, it’s important to consider questions about collective progress and the assumptions driving anti-corruption work considering the continuing extent of corruption and impunity … it is time to reorient around a small number of global advocacy priorities on which the Movement can make a sustained push for change. This will be dependent on sharpening advocacy approaches and moving towards more effective staffing and resourcing.”

In 2012, an evaluation of TI Latin America’s advocacy work made a related diagnostic and prescription “the anticorruption policymaking environment in the region has changed at a faster pace than advocacy. In the early 1990s, advocates were able to speak of a public policy vacuum in the anticorruption arena … In the 2000s, project-based islands of integrity produced some additional results … the 2010s pose a different challenge.” At the heart of the challenge is strategically focusing on multi-stakeholder collaborative efforts bringing about concrete and effective policy changes that fit and transform the anticorruption environment in the region.

How to design campaigns that are cognizant of the pensioners in Rio de Janeiro, the judicial struggles in Brasilia, and what we are learning as a field?

An opportunity to learn about doing next generation advocacy

Transparency International Brazil has acted on these cues. In 2018-TI-BR, in partnership with FGV’s Law School, have implemented an innovative anticorruption campaign focused on policy action and targeted at citizens and elites that are aware about the negative consequences of corruption: the United against Corruption or 70 measures against corruption campaign.

In January and February 2019, we will carry out a reflective exercise TI-BR to learn more about the decisions, trade-offs, opportunities and challenges, and lessons of putting together a broad multi-stakeholder anticorruption campaign in a polarized environment. The goal is to provide food for thought to help groups in Brazil who are interested taking the 70 measures to their state and local-level work. We will also be working on guidance for groups in other countries who might be interested in figuring out whether and how to adapt the campaign to their own realities – responding to appetite at two recent events in Washington (here and here).

So, if you are part of one of these groups: What would you like to know about doing next generation anticorruption advocacy? What aspects of designing, implementing or evaluating a next gen anticorruption campaign keep you awake at night? Send us your questions by twitting us @guerzovich & @ChiesSchommer with the hashtag #nextgenACadvocacy.